Like all reputable clinics, the UK scoliosis clinic focuses the majority of its time and effort on providing the best possible treatment for scoliosis cases. For the most part, this means keeping up with the latest research, bracing and exercise based techniques which can assist in controlling and reducing scoliosis, however, where we also concentrate a lot of time and attention is to the psychological aspects of living with and being treated for scoliosis.

Scoliosis and Psychological factors

Like any condition, Scoliosis can obviously cause distress and concern – but there are some specific factors associated with scoliosis which may make the condition especially difficult for many patients to cope with. The key areas include:

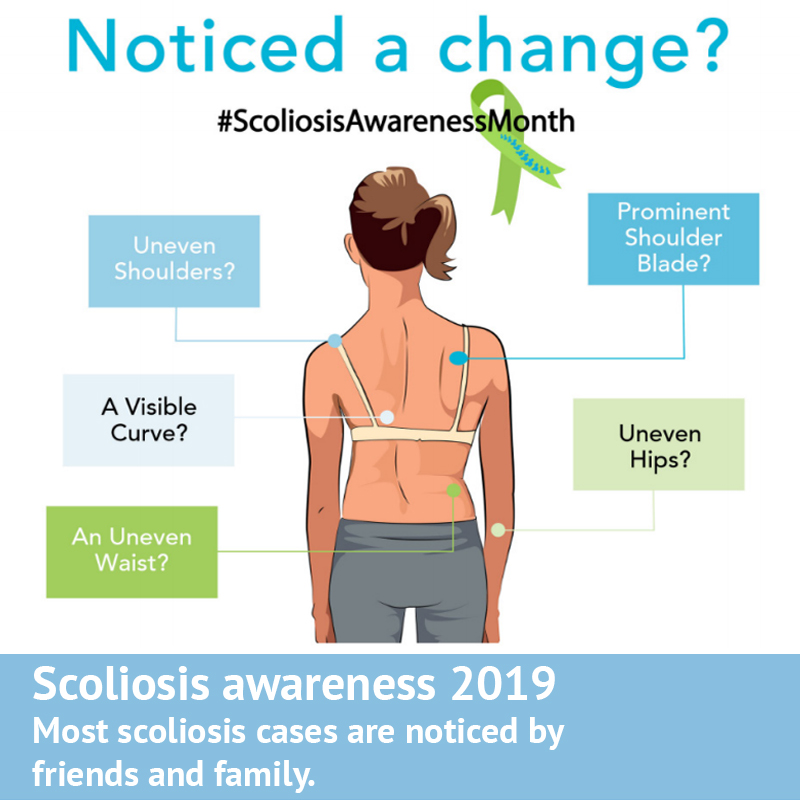

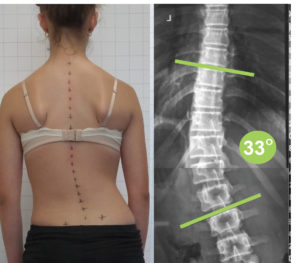

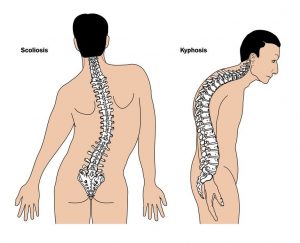

- The fact that Scoliosis does cause physical deformity, and very often strikes at the most sensitive time in a young person’s life. It’s normal and expected for teens and young adults to experience stress and difficulty associated with physical changes in their body and the formation of their adult identity, even under typical circumstances – scoliosis can certainly complicate this.

- Misinformation about scoliosis which is frequently repeated. Many still believe that a diagnosis of scoliosis necessitates surgery, which, ironically, can prevent some people from taking advantage of screening. It’s also commonly believed that scoliosis can impact on the ability to have children, take part in physical activity or even live a normal life. While it’s true that if left untreated scoliosis could lead to some of these outcomes, early treatment can often make such outcomes almost completely avoidable.

- Concerns about bracing, and stigma associated with bracing. It’s certainly the case that “old style” braces such as the Boston brace were visible, clunky and certainly embarrassing for young people – but modern CAD/CAM braces, such as ScoliBrace, are virtually invisible under clothing.

- Fear of being unable to participate in normal activities. Again, with modern bracing technology this is rarely if ever, an issue – today’s braces are so easy to put on and take off that they can simply be removed for exercise, although designs such as ScoliBrace are actually flexible enough to be left on.

With each of these concerns, the critical point to stress is that Scoliosis, if caught early enough can now usually be treated non-surgically and quite quickly, through bracing, exercise or a combination of both. The best possible way to detect scoliosis is through a routine screening, which can often allow the condition to be detected long before it has progressed to a significant degree.

Scoliosis and psychological health : scientific research

There has been some limited research which has sought to understand the impact that scoliosis can have on a young person’s psychological health – although it’s still fair to say that only a small part of the literature relating to scoliosis considers this angle, there is still sufficient a body of evidence for us to draw some meaningful conclusions.

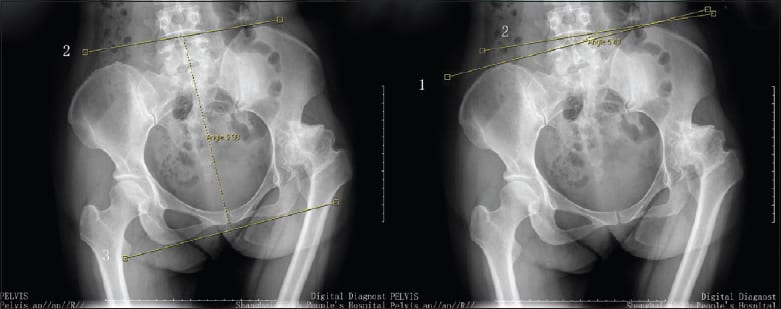

One such study looked at adolescents with and without scoliosis in Minnesota who were 12 through 18 years of age. During the study, six hundred eighty-five cases of scoliosis were identified from the 34,706 adolescents. The prevalence was therefore 1.97% (incidentally, this is slightly below the average figure). The researchers wanted to calculate the odds ratio of scoliosis to some common psychological issues.

Put simply, an odds ratio is a measure of how strongly related two items are – An odds ratio of more than 1 means that there are a higher odds of property B happening with exposure to property A, whereas an odds ratio of exactly 1 means that exposure to property A does not affect the odds of property B. An odds ratio is less than 1 is associated with lower odds of two factors being related. [1]

In the study, of the 685 adolescents with scoliosis, the odds ratio for having suicidal thought among adolescents with scoliosis, compared to adolescents without scoliosis, was 1.40 after adjustment for race, gender, socioeconomic status, and age. The odds ratio for having feelings about poor body development among adolescents with scoliosis was 1.82 compared with adolescents without scoliosis after adjustment for race, gender, socioeconomic status, and age. Scoliosis was therefore deemed to be an independent risk factor for suicidal thought, worry and concern over body development, and peer interactions.

In a 2019 study, which compared scoliosis treatment approaches, the SRS-22 (a standardised scoliosis quality of life screening form) was used to explore the impact which treatment had on psychological health. Here, researchers noticed that self-image was significantly improved amongst patients treated with a scoliosis brace, especially at a follow up after 12 months of treatment, this was especially interesting given the negative self-image association which is sometimes linked to bracing

Researchers found a similar improvement in patients treated with an exercise methodology – all the SRS-22 quality of life subsets showed a slightly larger improvement across the three visits than bracing, although the correction of scoliosis was less.[2]

Does scoliosis affect psychological health?

From the research which has been conducted, as well as our own experience at the clinic we feel it’s safe to say that scoliosis can be a significant risk factor for psychological health – especially in young people. While this certainly does not mean that everyone with scoliosis will struggle with mental health as a result, it’s clearly important that scoliosis clinicians are aware of the risk, and work to mitigate it.

At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we believe that properly researched information, coupled with effective treatment, applied as quickly as possible is the best possible way to address the psychological risks associated with scoliosis. It’s for this reason that we continue to recommend frequent screening throughout high risk years. It cannot be stressed enough that early detection, coupled with good information can go the majority of the distance in diffusing some of the main concerns around a scoliosis diagnosis. We would caution parents and sufferers from relying on general advice or information pulled from the internet – the best option is by far a consultation with a scoliosis professional.

[1] Payne, William K. III, MD, et al. Does Scoliosis Have a Psychological Impact and Does Gender Make a Difference? Spine: June 15, 1997 – Volume 22 – Issue 12 – p 1380–1384

[2] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]