Nearly three years ago we posted an article entitled “14 Myths about Scoliosis” – and by all accounts, it’s one of our most-read articles of all time. Perhaps there’s something about myth-busting, which is especially needed in the scoliosis world. Three years ago, we pointed out that much of what we know and understand about scoliosis is based on emerging research, or out of date information – scoliosis treatment is a rapidly advancing field, in which the best clinics need to stay on top of the technological and research developments.

After just a few years, this week, we revisit the 14 myths to see what we can add.

Myth 1 – Scoliosis causes pain

In 2017 we wrote that “while Scoliosis may be associated with pain as it develops, typically, scoliosis in the early phases does not cause pain. This is why scoliosis screening is so important, and why we provide the scoliscreen app. In Children especially, the early onset of scoliosis might go completely unnoticed.”

This has been perhaps the biggest change on the list – really, this no longer belongs on a list of “Myths” – to be clear, research now suggests that scoliosis does cause pain, at least in some cases. Certainly, we can no longer assume that the presence of pain means scoliosis is not a factor to consider.

This view was mostly based on older research, which had gone mainly unchallanaged for decades. Since then there has been a great deal of study on pain in scoliosis, so that today, we’re of the view that pain is, in fact, often a symptom of scoliosis. Research has now shown that Spinal pain is a frequent condition in AIS patients, further supporting the need for early detection and screening to minimise potential pain and suffering[1] – that In patients under 21 treated for back pain, scoliosis was the most common underlying condition[2] and that in one study of 2400 patients with AIS, 23% reported back pain at their initial contact[3].

Studies have also shown that s coliosis patients have between a 3 and 5 fold increased risk of back pain in the upper and middle right part of the back[4] , that Chronic nonspecific back pain (CNSBP) is frequently associated with AIS, with a greater reported prevalence (59%) than seen in adolescents without scoliosis (33%)[5] and that patients diagnosed with AIS at age 15 are 42% more likely to report back pain at age 18.[6]

Myth 2 – “Watchful waiting” is the best approach

In 2017 we wrote: “In the UK and many other parts of the world a “wait and see” approach is often favoured when it comes to scoliosis. The condition is monitored to see if it gets worse, with a view to undertaking a surgical fusion of the spine if the situation becomes bad enough.

In the past, this might have been the best approach, but today we have the know-how and technical ability required to create a scoliosis specific exercise program and a customised bracing solution, which can serve to correct the problem before it progresses to the point where surgery would be required. It is easier to improve a more flexible and smaller curve with bracing and scoliosis specific exercise than it is to change a large more rigid curve – so early diagnosis and appropriate treatment make a big difference.”

Since 2017 we’ve discussed the cost benefits of early screening on a number of occasions – bracing and treatment costs have come down meaning that early detection and treatment makes all the more sense financially.

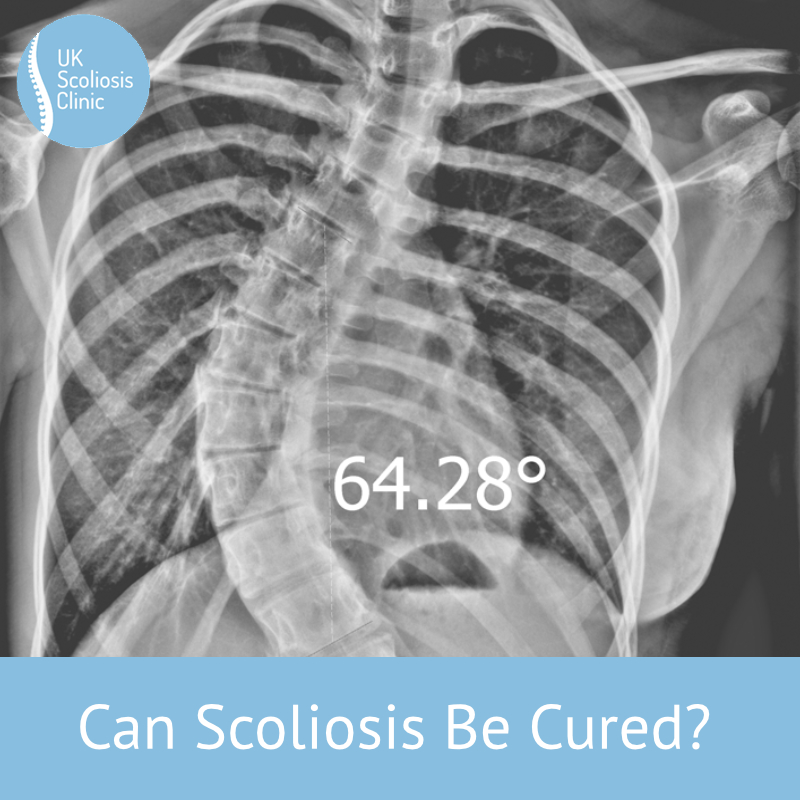

Earlier this year, we reported that many specialists still take the view that scoliosis can only be treated surgically (this is false!), in many cases you may not be seen by a specialist until scoliosis has developed beyond 45 degrees, which is typically considered the threshold for surgery. Bracing and other non-surgical methods are certainly still possible in curves up to 60 degrees depending on the individual case and risk of future progression.

Recent research by the British Scoliosis Society (BSS) has now illustrated just how long “wait and see” can go on, even after getting an appointment for a consultation. They showed that most patients face another long wait for treatment during which scoliosis tends to progress. Their 2018 study specifically looked at scoliosis progression whilst waiting for a consultation and eventual surgery. In the study, 41 females and 20 males with a mean age of 11.8 years with a mean Cobb angle (curvature) of 58° were followed – Average waiting time to be seen in the clinic for an initial consultation was 16 months – thereafter, the average waiting time for surgery was 10 months. Rapid curve progression was seen in twelve patients, of which 10 required more extensive surgery than originally planned. Their mean Cobb angle at presentation was 48° which increased to a mean of 58° at surgery[7]. Many of those cases could have been treated non surgically before the “waiting” – but probably not after.

Myth 3 – Scoliosis screening doesn’t help scoliosis sufferers

In 2017 we wrote: “Current UK policy does not support mass screenings due to the cost, potential of false positives, belief that bracing doesn’t work and that if the curve is severe enough family or other adults will notice it.

As we mentioned above, since scoliosis does not always cause pain (and most people don’t know how to recognise scoliosis anyway) it’s entirely possible that the condition can go unnoticed in many cases. The earlier the detection, the more appropriately the right treatment can be given at the right time.”

Research continues to support the need for early screening, although we do now recognise pain as a symptom. Newer online screening tools (including our own, which will be released soon) are helping to make screening faster, and easier than ever before – the scoliosis treatment community will probably resolve this issue through technology long before government takes any action.

Myth 4 – Scoliosis doesn’t progress into adulthood

In 2017 we wrote “Historically, scoliosis was most strongly associated with growth – from this it was assumed that when an adolescent stops growing, scoliosis would not progress. It is now known that it often will progress into adulthood – in addition, the bigger the existing curve the more likely it is to progress.

The major reason for progression is the weakening of the ligaments in the spine as we age. As the ligaments weaken, the spine loses stability and the spinal deformity worsens. This means that appropriate exercises and chiropractic care are highly beneficial for us all as we age – but can make a huge difference to a scoliosis sufferer.

The weakening of ligaments causes 30% of the population over the age of 60 years to have scoliosis versus only 3% of adolescents!”

Since 2017, we’ve successfully treated many older adults suffering from degenerative scoliosis – and we’ve seen first hand the positive effects such as a reduction in pain, even from part-time bracing – in this sense, our results are in line with the research which was emerging back in 2017.[8]

Myth 5 – Swimming will help reduce scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote “Over many years children have been told to swim to treat scoliosis. While swimming is a great form of exercise in general, there is no evidence to support this idea – although there actually has been some research which suggests that scoliosis can be worsened after swimming. This research is not strong enough to suggest that scoliosis patients should avoid swimming, but we can now say that swimming alone is not an effective treatment.”

Since then, we aren’t aware of any studies which have specifically looked at swimming – and this is mainly because there is much greater focus on scoliosis specific exercises which can help to control or reduce Scoliosis in a significant way.

Myth 6 – Bad posture causes scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote that “You might think that telling your child to sit upright will stop scoliosis – this makes sense since often adolescents will have slumping posture, however, the slumping posture itself is not necessarily linked to the development of scoliosis.

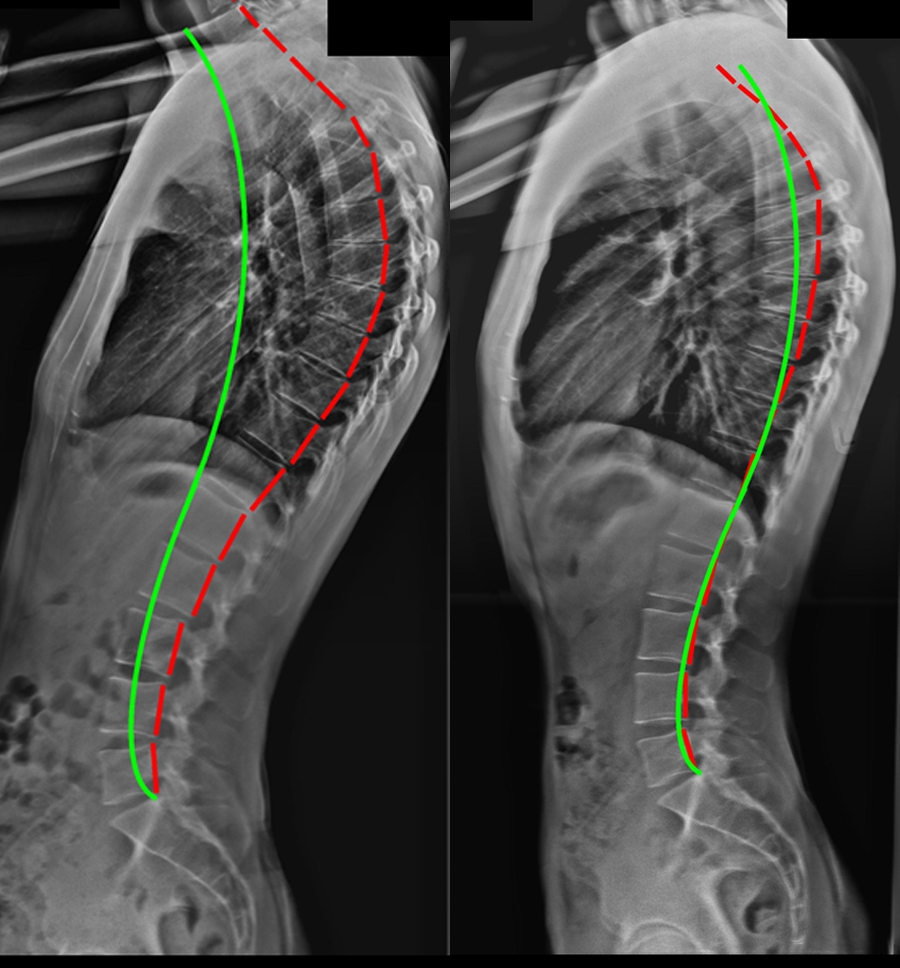

In fact, for children with scoliosis, the spine will often be straighter than is observed in the average population. Typically, the thoracic kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis will be reduced and sometimes even bend in the opposite direction!

Often children’s shoulder blades will lift off the thorax (aka winging of the scapula) due to weakness of the serratus anterior muscle which will give the appearance of hunching.”

The only point we would add here today is that the advances in research around pain and scoliosis are significant for teens and young adults – if your child is complaining of back pain, we now advise that you seek the help of a spinal professional, at least to rule out scoliosis. A consultation with a scoliosis practitioner is ideal – but most professional chiropractors will be able to provide you with an X-ray which could show early signs of scoliosis. If your child shows any kind of unusual posture, we recommend scoliosis screening as soon as possible.

Myth 7 – You can correct scoliosis by just sitting up straight

In 2017 we wrote “Scoliosis is more than just twisting of the spine, it causes is often multi-factorial thus a multi-factorial treatment must be given. Sitting up straight might help a little since postural exercises might well be an effective element of a treatment program, but the right treatment will be different for every patient – that’s why we take time to go through a detailed consultation process with each patient.”

It’s still true that you can’t correct scoliosis by changing your sitting patterns – but with higher than ever levels of young people coming into our clinic with neck problems, it’s worth keeping in mind. Long term postural problems could predispose you to the development of de-novo scoliosis later in life – so a focus on posture now may pay dividends later.

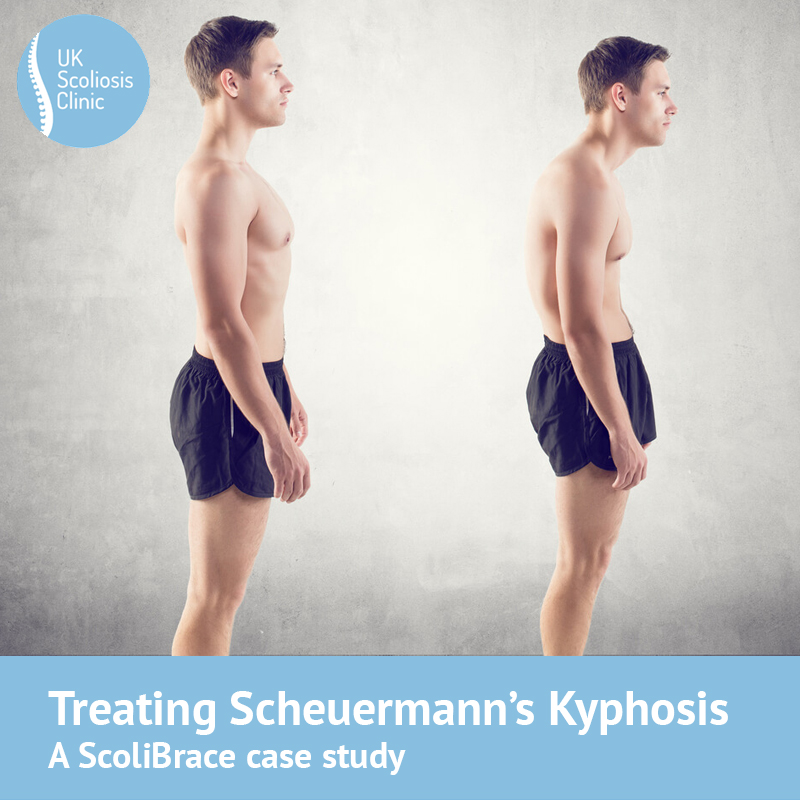

Myth 8 – Spinal braces don’t work in correcting scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote that “Spinal bracing has been the subject of intense research over the past 15-20 years. Far from the myth that they are ineffective, spinal braces have been shown to reduce progression in 70 to 80% of cases compared to those who aren’t braced.

Among some healthcare professionals, the notion that scoliosis braces don’t work does still exist however this is most usually because there is confusion about the kind of bracing being discussed. Bracing technology itself has come a long way in the last few years. Traditional medical braces are designed to hold the spine in the patient’s scoliotic position, which might halt progression, but it actually does nothing to improve the curve.

In contrast, our Scolibrace braces are an active over-corrective brace which works to shift the spine in the opposite, direction back towards normal posture. In addition, they help to shift the mechanical loading of the spine to stimulate normal spinal growth. This not only helps to reduce the likelihood of progression but also improves the potential correction.

Traditional braces, therefore don’t work in correcting scoliosis (although they might stop it getting worse) Scolibrace braces, however, actively work to correct the position of the spine, and have been shown to be highly effective in doing so.”

In recent years there has been yet more improvement in bracing technology, with research to further explore its effects being published regularly. Since 2017, it’s been established that Bracing is far more effective than exercise in reducing cobb angle. In one study, the 6-month reduction in Cobb angle from a bracing group was 3.13 degrees and at 12 months the mean reduction was 5.88 degrees. In the exercise group, the 6 months mean reduction was just 0.66 degrees, and at 12 months was 2.24 degrees[9] There’s no question that the exercise approach still have value – not least because they address the muscular imbalances that bracing does not – but today, we recommend bracing to most of our clients, either full time or part-time.

Myth 9 – Scoliosis only affects girls

In 2017 we wrote “Scoliosis is more common in girls than boys, but boys can and do develop scoliosis.

Scoliosis is particularly common in ballet dancers and gymnasts, which might be at the heart of this misconception, but there is no doubt the boys and girls can both develop scoliosis.”

Our experience since then shows this to be true – more girls than boys experience scoliosis, but we have seen many male patients of all ages at the clinic. To be a little more specific on the Gymnastics question, research has shown that Gymnasts (and ballet dancers) are as much as 12 times more likely to develop scoliosis than non-gymnasts[10] however, we still urge caution with this statistic – we’ve discussed this issue a few time since 2017, and each time we’ve noted the awareness of scoliosis in these fields, which doubtless leads to higher reporting.

Myth 10 – Spinal manipulation can reduce scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote that “Spinal adjustment and manipulation can often help to improve spinal mobility and ease areas of aches and pains in those who have scoliosis, just as it can for those who don’t – but spinal manipulation alone will not reduce scoliosis.

While chiropractic adjustments can form a valuable part of an overall treatment regime, there is no evidence from the scientific literature to support the assertion that spinal manipulation and adjusting techniques alone can reduce scoliosis. Where adjustments may be highly beneficial is in support of an exercise and lifestyle regime, as a method of increasing range of motion, and reducing pain in some cases.”

Over time, serious research into chiropractic based treatment as an approach to reducing scoliosis has been coalescing around the CLEAR institute, who have certainly published some interesting research. In a sample of 140 patients using the prospective CLEAR technique, (and according to the CLEAR institute themselves) improvement in Cobb angle was documented in all 140 cases. The average amount of reduction in Cobb angle was 37.7% after an average of 12.3 visits. 23 patients were no longer classified as having scoliosis after their treatment (e.g., the Cobb angle was reduced to below 10 degrees).

While the study results were published[11], they were not peer-reviewed and therefore do not currently meet the standard of proof for us to consider this technique at the UK Scoliosis Clinic – we will keep this under review, however, should independently reviewed research become available.

Myth 11 – Physiotherapy exercise reduces scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote: “Just like chiropractic care, physiotherapy can help to improve mobility and function for scoliosis patients and might form part of an overall program – however again there is no evidence to show that generalised exercise, massage, mobilisation or core stability will improve a scoliotic curve. Bracing and scoliosis specific exercise are currently the only non-surgical methodologies which is clinically indicated as effective in treating scoliosis.”

As outlined above, this still holds true – we believe that scoliosis specific exercise is a solid approach for treating small curves, and for addressing issues around muscular imbalance and some kinds of pain associated with scoliosis. Research continues to show that a combination of both approaches is greater than the sum of its parts. Interestingly, research since 2017 has demonstrated that exercised based approaches tend to yield a slightly higher quality of life scores (SRS Questionnaire-based) than bracing alone[12].

Our view is now that Bracing is the primary tool for reducing Cobb angle – exercised based approaches are an invaluable “force multiplier” in this regard.

Myth 12 – Heavy backpacks cause scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote that “Heavy backpacks cause uneven loading and are never good for children’s spines and posture… but they don’t cause scoliosis. If it was the case every child would have scoliosis!”

This is still the case – but please do be kind to you child and think about their spine health overall, not just scoliosis!

Myth 13 – Scoliosis worsens in pregnancy or will stop me having children

In 2017 we wrote that “Current research knowledge shows that women are not at an increased risk of progression in pregnancy, however carrying a baby will produce more stress upon the body and the spine which will increase the likelihood of pain and discomfort as for all women in pregnancy.

At birth, it is important for the anaesthetist to be aware that a mother has scoliosis, as it will affect the position of the spine if they need to give an epidural injection. It will not however affect the woman’s ability to carry a child or give birth.”

Again this position I unchanged – Scoliosis will not affect your fertility.

Myth 14 – Surgery is the only treatment for scoliosis

In 2017 we wrote that “Surgery is sometimes the only option for large curves at high risk of progression. 50 degrees is the typical indicator for surgery as the curve is at a high risk of progression into adulthood.

Scolibrace with scoliosis specific corrective exercise has been shown to be clinically effective in reducing curves between 20 and 60 degrees, whereas curves between 10 and 20 degrees with a low risk of progression can sometimes be treated by scoliosis specific exercise alone.

As previously mentioned early diagnosis is key, as the chances for arresting and correcting a relatively small angle are very good.”

Since 2017, we’ve helped patients from all backgrounds, ages and genders beat scoliosis – and in the vast majority of cases, we have been able to help them avoid surgery. Where this hasn’t been possible, it is almost always because they sought treatment too latte – had scoliosis been caught sooner, a non-surgical option would almost always have been open to them.

As always, screen regularly – and if you have questions get in touch – don’t wait and see!

[1] ‘Back Pain and Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: A Descriptive, Correlation Study’,

Theroux Jean, Le May Sylvie, Labelle Hubert [University of Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Murdoch University, Perth, WA, Australia], Spine Society of Australia 27th Annual Scientific Meeting (8-10 April 2016)

‘Back Pain Prevalence Is Associated With Curve-type and Severity in Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis A Cross-sectional Study’

Jean Theroux, DC, MSc, PhD, Sylvie Le May, RN, PhD, Jeffrey J. Hebert, DC, PhD,and Hubert Labelle, MD : SPINE 153607

[2] Dimar 2nd JR, Glassman SD, Carreon LY. Juvenile degenerative disc disease: a report of 76 cases identified by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine J. 2007;7:332–7.

[3] Ramirez N, Johnston CE, Browne RH. The prevalence of back pain in children who have idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:364–8

[4] Sato T, Hirano T, Ito T, Morita O, Kikuchi R, Endo N, et al. Back pain in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: epidemiological study for 43,630 pupils in Niigata City. Japan Eur Spine J. 2011;20:274–9

[5] Jean Theroux et al. Back Pain Prevalence Is Associated With Curve-type and Severity in Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis Spine: August 1, 2017 – Volume 42 – Issue 15

[6] Clark EM, Tobias JH, Fairbank J. The impact of small spinal curves in adolescents that have not presented to secondary care: a population- based cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016; 41:E611–7.

[7] H V Dabke, A Jones, S Ahuja, J Howes, P R Davies, SHOULD PATIENTS WAIT FOR SCOLIOSIS SURGERY? Orthopaedic ProceedingsVol. 88-B, No. SUPP_II

[8] Scoliosis bracing and exercise for pain management in adults—a case report

Weiss et al, J Phys Ther Sci. 2016 Aug; 28(8): 2404–2407

[9] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]

[10] ‘Prevalence and predictors of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in adolescent ballet dancers’

Longworth B., Fary R., Hopper D, Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014 Sep;95(9):1725-30. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.02.027. Epub 2014 Mar 21.

[11] Woggon D, Woggon A, and Chong S: Developing a scoliosis-specific chiropractic protocol: preliminary results from 140 consecutively-treated scoliosis cases. The American Chiropractor, Dec 2013; 35(12):16-22.

[12] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]