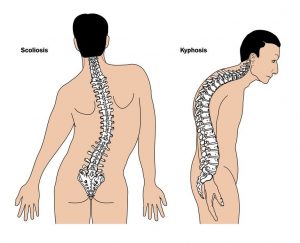

A number of the conditions we treat here at the clinic (but most commonly Scoliosis and Kyphosis) are often treated at least in part with an exercise program. In some cases, the exercise program might be a primary line of treatment, whereas in other instances it is used as a support mechanism.

Here at the clinic, we will usually provide an exercise prescription which patients should then undertake each day at home. Sometimes this is the correct approach, but one of the most significant problems posed by this approach is exercise adherence. The simple fact is that programs such as Schroth or SEAS do not work if they are not performed every day and for the correct amount of time.

At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we work to avoid this problem by staying in touch with our patients and scheduling regular check-up appointments, but exercise adherence is still a significant factor in determining treatment success.

In recent years, it has often been argued that either an app or computer program might replace the role of the clinician in encouraging exercise adherence. It’s certainly an attractive idea, however as yet, the research indicates this approach is not practical.

There’s an app for that

There’s no question that augmenting face to face treatment with software-based approaches has great promise, and it certainly stands to reason that apps could have the potential to play an essential role in promoting exercise adherence in the future. Apps can monitor patients remotely, are cheap, can provide reminders, and can enable feedback to patients. Many of us also now use apps for fitness purposes, either as exercise trackers, heart rate monitors or in place of a traditional personal trainer. Despite this, app-based exercise programs have not been widely incorporated in rehabilitation for adolescents with musculoskeletal disorders[1]

So far, research has not suggested that apps have been particularly effective as a replacement for traditional contact with professionals more generally – a recent systematic review showed limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of using apps to increase physical activity in adolescents[2]. Furthermore, apps aimed at increasing physical activity in adolescents were not effective[3].

Exercise adherence in Hyperkyphosis

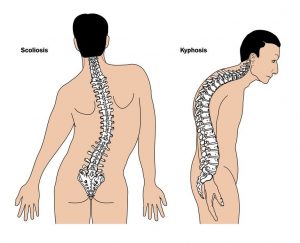

Scoliosis and Kyphosis can both be disruptive conditions

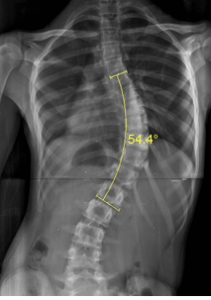

One of the conditions we treat at our clinic is Hyperkyphosis. While hyperkyphosis is sometimes seen as less serious than Scoliosis, research shows that adolescents with hyperkyphosis have decreased quality-of-life (particularly the self-image and appearance components[4]. Hyperkyphosis is also associated with back pain in long-term follow-up studies[5]. Hyperkyphosis is often treated with an exercise prescription, either in advance of bracing or as a complementary approach. Milder cases of Hyperkyphosis have been shown to respond well to exercise-based programs – although the biggest issue is ensuring that patients adhere to their exercise plan.

A Kyphosis case study

Given that few attempts have been made to use apps specifically to treat musculoskeletal conditions, a recent study was set up to assess the potential of an app-based exercise program for adolescents with Hyperkyphosis and back pain[6].

App usage was not impressive in the study

The study focused on 21 participants, between 10 and18. All of the participants were given an initial one-time exercise treatment session and were instructed to continue using an app provided for the study to track and guide their home-based exercise over a period of 6 months.

After participants logged in to the app, they were shown their prescribed exercises by image and exercise name. To perform an exercise, users only had to click on the exercise, which shows the same picture and written instructions on how to perform the exercise. The prescribed amount of time counts down similar to an interval timer while the participant performs the exercise.

Although the format was relatively simple, and the exercise sessions prescribed only lasted approximately 15 minutes a day, the study shows that most participants did not use the app. One participant did not have a Smartphone or tablet, this participant did participate in the exercise program, and logged exercise adherence on a sheet of paper. One participant complied with the program 100%, but the remaining participants either did not use the app or used it less than once per week. When investigators questioned the participants about their usage, they also indicated themselves that they used the app less than weekly. Unsurprisingly, the patient’s quality of life scores (measured with the SRS-22 form) did not significantly improve over the 6 months.

What can we learn from these results?

These results serve mainly to confirm what has been suspected for some time – many users just do not stick to their exercise program, absent encouragement and mentorship from scoliosis or kyphosis professional. For parents of children with kyphosis or scoliosis, the critical question is therefore whether exercise-based approaches are the most suitable treatment, given that adherence to the program is so important. In some instances, parents may prefer to opt for a kyphosis or scoliosis brace, which does not suffer from these same issues.

Does this mean apps are useless in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders? Almost certainly not – some apps, such as our ScoliScreen allow users to perform an initial diagnosis of their scoliosis, and monitor their conditions. The study discussed here did also show that the app had a positive effect on the study participant who fully committed to the exercise program, which suggests that a combination of an app and personal encouragement from a clinician may be a superior way forward. At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we are always researching the best way to give a superior experience to our patients, and apps are a field that we are investigating with interest!

[1] Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Teens and mobile apps privacy. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2013. [2015-04-21].

[2] van Sluijs EMF, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ. Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;335(7622):703.

[3] Direito A, Jiang Y, Whittaker R, Maddison R. Apps for IMproving FITness and increasing physical activity among young people: the AIMFIT pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(8):e210.

[4] Petcharaporn M, Pawelek J, Bastrom T, Lonner B, Newton PO. The relationship between thoracic hyperkyphosis and the Scoliosis Research Society outcomes instrument. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(20):2226–31.

Lonner B, Yoo A, Terran JS, et al. Effect of spinal deformity on adolescent quality of life comparison of operative Scheuermann’s kyphosis, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and normal controls. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(12):1049–55.

[5] Murray P, Weinstein S, Spratt KF. Natural history and long-term follow-up of Scheuermann kyphosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75A(2):236–48.

Ristolainen L, Kettunen JA, Heliövaara M, Kujala UM, Heinonen A, Schlenzka D. Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: a 37-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(5):819–24.

[6] Karina A. Zapata, Sharon S. Wang-Price, Tina S. Fletcher and Charles E. Johnston Factors influencing adherence to an app-based exercise program in adolescents with painful hyperkyphosis Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders 201813:11