Today the two main methodologies involved in the non-surgical treatment of scoliosis are Bracing, and Specialist exercise methodologies. In most cases we use both approaches throughout the course of treatment with our patients since both approaches have their strengths. We are however, often asked which treatment methodology is best – so let’s consider the latest research on this question.

Bracing vs Exercise – New research

The first thing to realise when comparing scoliosis treatment is that while many patients often want to know “which is best”, this question is often less explored in the scientific literature. For the most part, scoliosis practitioners want to focus their time and attention towards improving their methodologies of choice, rather than on making comparisons with other approaches. Because of this, few studies have tried to directly compare bracing and exercise approaches – although a recent 2017 study has done just this[1].

In the study conducted in China, 53 patients (age of 10 – 17 years, Cobb angle ≥ 20 – 40 degrees,) were randomly assigned to either a bracing group or exercise group. Twenty-four patients (19 females) were placed in the bracing group and 29 patients (22 females) in the exercise group.

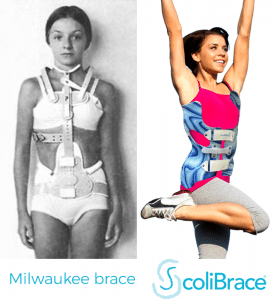

Patients in the bracing group were provided with a rigid thoracolumbosacralorthosis (a Scoliosis brace – TSLO) and asked to wear their brace 23 hours a day, while patients in the exercise group were treated with the Scientific Exercise Approach to Scoliosis (SEAS) protocol. Data regarding angle of trunk inclination, Cobb angle, shoulder balance, body image, quality of life (QoL)[2] were collected every 6 months.

At the first visit, patients assigned to the bracing group were prescribed with a rigid (TLSO) and received an initial pre-treatment evaluation to allow for brace fabrication. To achieve optimum correction, patients were invited to the scoliosis clinic to check the fit and modify (if necessary) the brace after the first month of intervention and then every three months as recommended by SOSORT[3].

The SEAS patients took part in a session of 1.5 hours at which they learned and practiced the core content of their program every two to three months, in which they learnt their personalised exercise protocol. The patients continued treatment at the clinic once a week (40 minutes) plus one daily exercise session at home (10-15 minutes)[4].

Study Results

At this stage, it’s important to mention that while this study represents an important beginning in this comparative project, the results available at this time reflect only a year of treatment. It is likely that the trends illustrated here will hold good over a longer period, and thankfully we will be able to verify this since the study is still ongoing.

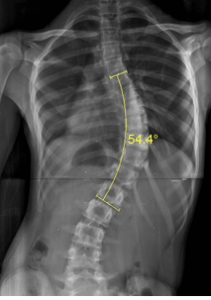

Cobb angle

The bracing group achieved a significantly larger reduction in Cobb angle – at 6 months, the mean reduction of cobb angle in the bracing group was 3.13 degrees, and at 12 months the mean reduction was 5.88 degrees. In the exercise group, the 6 months mean reduction was just 0.66 degrees, and at 12 months was 2.24 degrees.[5]

Quality of Life

The SRS-22 form used for gauging quality of life factors consists of a number of subsets of data, each of which was individually evaluated during this study. These include a score for pain, function, mental health and self-image. Taken as a whole, the results showed that for the bracing group, the SRS functional score (a measure of the impact of scoliosis on everyday life) as well as the total score (a broader measure of quality of life factors) all showed significant improvement between the initial consultation and 12-month evaluation as well as between the 6-month and 12-month evaluations. The one exception to this was pain level, which did not differ significantly across the three evaluations.

The researchers also noticed that self-image was significantly improved in the bracing group, especially at the 12 months follow up, this was interesting given the negative self-image association which is sometimes linked to bracing. Participants did report an increase in their overall satisfaction levels (taking all factors into account), although this was most apparent after passing the 6-month mark.

For the exercise group, all the SRS-22 quality of life subsets showed a slightly larger improvement across the three visits than bracing – especially in terms of the functional score. The exception here again was pain, where no significant change was detected[6].

Overall comparison

In comparing the two treatment groups, the study investigators noted it was interesting to find that the overall improvement of quality of life was more significant in the exercise group. Although the quality of life scores improved in both groups, at all three visits, the average scores of most subsets in the SRS-22 were higher in the exercise group. By contrast, the improvement in cobb angle was significantly greater in the bracing group, although the exercise group did also show an improvement at the 12-month mark.

So which is better?

At this stage, it seems fair to suggest that the results of the study reflect what many scoliosis clinicians are already aware of – Scoliosis Bracing is by far the most effective way to reduce a cobb angle – Indeed, the authors note how “There is no doubt that bracing has proven efficacy in halting the progressive nature of the deformity and reducing the need for surgery”.

At the same time, scoliosis specific exercise has a more positive impact on functional capacity – this comes as no surprise to scoliosis practitioners, since scoliosis specific exercise is intended to reduce muscular imperfections and promote better everyday posture. Exercise approaches also seem to correlate with a greater improvement in quality of life factors than bracing, although this is also to be expected since it is almost universally accepted that any form of exercise serves to boost quality of life in most individuals.

Taking these two points, its easy to see how a combination approach is often the best possible option – by pursuing both treatment methodologies it is possible to achieve functional improvement, cobb angle correction and an improvement in quality of life in a flexible way which works for the patient.

More results from this particular study, as well as further research can be expected in this area and we will report it to you as soon as it becomes available!

[1] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]

[2] The SOSORT SRS-22 Form was used for this data collection.

[3] Negrini S, Aulisa AG, Aulisa L, et al. 2011 SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis 2012;7:3.

[4] Romano M, Negrini A, Parzini S, et al. SEAS (Scientific Exercises Approach to Scoliosis):a

modern and effective evidence based approach to physiotherapic specific scoliosis exercises. Scoliosis 2015;10:3.

[5] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent

idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]

[6] Yu Zheng, MD PhD et al. Whether orthotic management and exercise are equally effective to the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Mainland China? – A randomized controlled trial study SPINE: An International Journal for the study of the spine [Publish Ahead of Print]