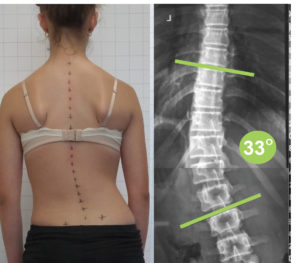

Scoliosis, if left untreated, tends to progress in most cases – and where this progression is significant enough it can result in significant disability and reduction in quality of life. For this reason, scoliosis is a condition which the medical profession has been keen to treat and treat as early as possible in affected individuals. Stopping scoliosis is the primary objective of any surgical procedure, but unlike non-surgical approaches, there are known complications with surgical interventions. One of the most common is Degenerative Disc Disease (DDD).

Treatment options for scoliosis

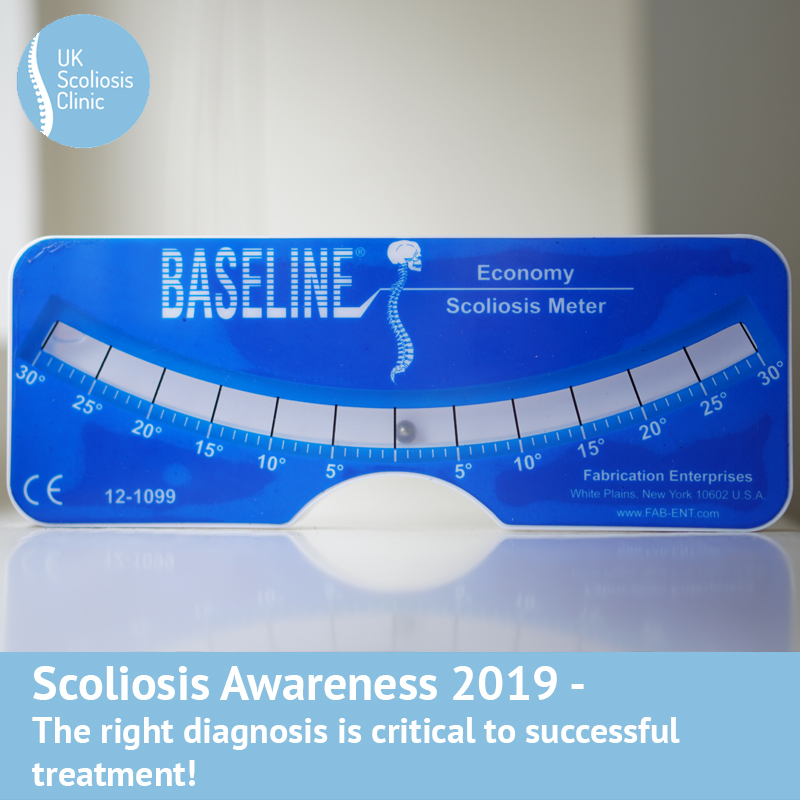

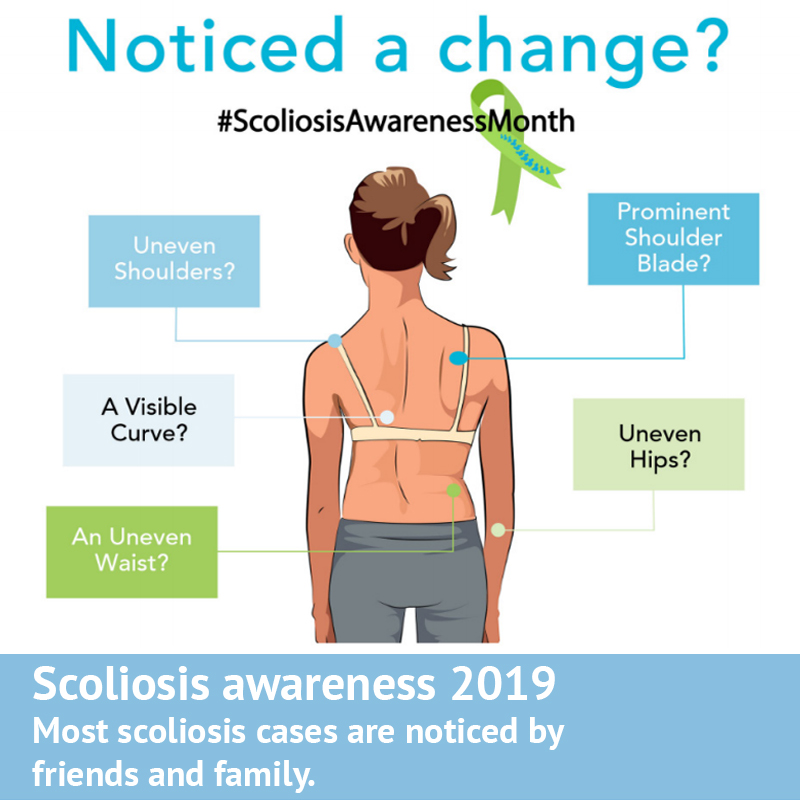

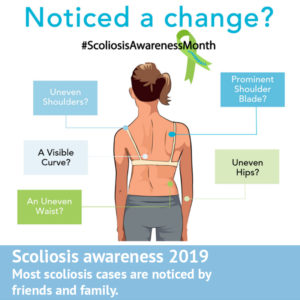

Today, the treatment options for Adolescent Idiopathic scoliosis include observation, bracing, exercise approaches and surgery, and the general goal is to keep curves under 50° at maturity[1]. Observation, while still recommended by some medical practitioners not specially trained in scoliosis management, is not truly a treatment for scoliosis, and instead simply allows the condition to progress. Non-surgical options, such as bracing and exercise are fast becoming the treatment of choice, with surgery usually preferred as a last resort.

There are three main approaches to scoliosis surgery – these are posterior spinal fusion (PSF), anterior spinal fusion (ASF), or a combination of both. In each case, the goal is to fuse the affected vertebra into the correct position – this results in the targeted vertebra being unable to move, instead fusing into a single unit, but also eliminates scoliosis. PSF remains as the gold standard for the treatment of thoracic and double major curves, which make up most scoliosis cases. ASF is indicated for thoracolumbar and lumbar cases having a normal sagittal profile. A combination of ASF and PSF could also be used for the management of large curves (> 75°) or stiff curves, young age, and to prevent the “crankshaft phenomenon” – a condition in which the posterior fusion of the spine cases a secondary curvature to form as the bones grow.[2]

Although the safety and efficacy of both techniques have been demonstrated[3], many patients and surgeons are increasingly concerned about the long-term outcome of an extensive fusion in terms of spinal function, the development of degenerative disc disease and pain[4]. Weiss et al. reviewed the long-term risks of fusion spinal surgery with respect to scoliosis to enable establishing a cost/benefit relation of this intervention. According to their study, average rate of complications was as high as 44% in adolescent cases, ranging from 10 to 78%. They concluded that long-term complications have not yet been fully evaluated and further studies are needed to address this concern adequately[5].

Post-operative complications – new research

Corrective surgery of AIS can result in several benefits for the affected patients including improvements in aesthetics, quality of life, disability, back pain, psychological well-being, and breathing function. This is especially the case for patients whose scoliosis has progressed beyond the range likely to be positively impacted by non-surgical approaches, such as bracing.

These points notwithstanding, surgery is also associated with a variety of complications whose long-term impact is currently poorly understood – these may include neurological damage, loss of normal spinal function, strain on unfused vertebrae, curvature progression, decompensation and increased sagittal deformity, increased torso deformity, delayed paraparesis, and pseudarthrosis.[6] Degenerative disc disease is however considered one of the most common results of surgery (although it is also associated with scoliosis progression) and its association with the severity of pain has been reported.[7]

The most recent study looking at this connection was published in 2018[8] and followed a total of 42 AIS patients who underwent PSF surgery. The participants were examined for a range of post-operative complications. The mean age of the surgery was 14.4 ± 5.1 years. The mean follow-up of the patients was 5.6 ± 3.2 years.

On the positive side, the study confirmed that complete fusion of the vertebra was observed in all cases, and no cases of failure of surgical implants were noticed – in this sense, the patient’s scoliosis cases were therefore addressed and halted, which was of course the primary objective. However, according to the most recent study, degenerative disc disease had developed in 6 out of 37 (16%) of the patients. This finding was roughly in line with previous research, which has suggested rates on average of 7%, although rates varied by study.[9]

More concerning however, was the fact that the observed post-operative disability tended to increase over time, a similar study by Upasani et al. also showed an increased pain at 5 years compared with 2 years after AIS surgical treatment[10], and with this in mind the study investigators suggest that possible progression of DDD and associated increases in pain be carefully considered before opting for a surgical procedure.

Treating scoliosis without surgery

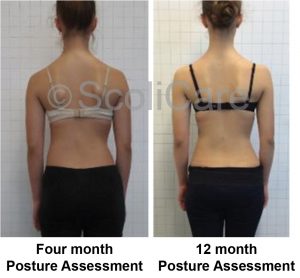

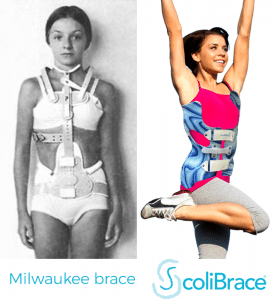

While it’s clear that for some patient’s surgical intervention may be the best option, even if there is a risk of postoperative complications, recent advances in non-surgical approaches to scoliosis treatment mean that other options exist for far larger numbers of patients then ever before. Scoliosis bracing, for example, is not associated with any long-term complications, save for the possibility of a loss of muscle strength, which is easily mitigated with targeted exercises. While such approaches are necessarily slower to show results than a surgical procedure, the most modern “over corrective” braces (such as the ScoliBrace we offer at the UK Scoliosis clinic) can nonetheless offer a substantial correction, typically over a period of 6 to 12 months.

[1] Janicki JA, Alman B. Scoliosis: review of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12:771–6.

Tari SHV, Mahabadi EA, Ghandehari H, Nikouei F, Javaheri R, Safdari F. Spinopelvic sagittal alignment in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Shafa Orthop J. 2015;2(3):e739.

[2] Hasan Ghandhari, Ebrahim Ameri, Farshad Nikouei, Milad Haji Agha Bozorgi, Shoeib Majdi & Mostafa Salehpour ,Long-term outcome of posterior spinal fusion for the correction of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis Scoliosis and Spinal Disordersvolume 13, Article number: 14 (2018)

[3] Wang Y, Fei Q, Qiu G, Lee CI, Shen J, Zhang J, Zhao H, Zhao Y, Wang H, Yuan S. Anterior spinal fusion versus posterior spinal fusion for moderate lumbar/thoracolumbar adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a prospective study. Spine. 2008;33:2166–72.

[4] Bridwell KH, Shufflebarger HL, Lenke LG, Lowe TG, Betz RR, Bassett GS. Parents’ and patients’ preferences and concerns in idiopathic adolescent scoliosis: a cross-sectional preoperative analysis. Spine. 2000;25:2392–9.

[5] Weiss H-R, Goodall D. Rate of complications in scoliosis surgery—a systematic review of the Pub Med literature. Scoliosis. 2008;3:9.

[6] Weiss H-R, Goodall D. Rate of complications in scoliosis surgery—a systematic review of the Pub Med literature. Scoliosis. 2008;3:9.

[7] Buttermann GR, Mullin WJ. Pain and disability correlated with disc degeneration via magnetic resonance imaging in scoliosis patients. Euro Spine J. 2008;17:240–9.

[8] Hasan Ghandhari, Ebrahim Ameri, Farshad Nikouei, Milad Haji Agha Bozorgi, Shoeib Majdi & Mostafa Salehpour ,Long-term outcome of posterior spinal fusion for the correction of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis Scoliosis and Spinal Disordersvolume 13, Article number: 14 (2018)

[9] Jones M, Badreddine I, Mehta J, Ede MN, Gardner A, Spilsbury J, Marks D. The rate of disc degeneration on MRI in preoperative adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2017;17:S332.

[10] Upasani VV, Caltoum C, Petcharaporn M, Bastrom TP, Pawelek JB, Betz RR, Clements DH, Lenke LG, Lowe TG, Newton PO. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients report increased pain at five years compared with two years after surgical treatment. Spine. 2008;33:1107–12.