When you’re dealing with scoliosis, the least important factor should be finances – you should always select a treatment plan based on it’s long term prospects and what’s best for you or your child. This being said, it’s true that the earlier Scoliosis is caught, the easier and (usually) more cheaply it can be treated. It’s for this reason that scoliosis screening can actually save you a great deal of money…..

Scoliosis screening is really cheap

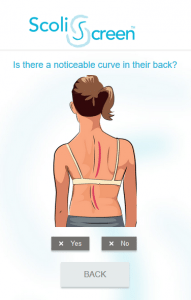

It’s certainly true that scoliosis bracing and even exercise-based therapies are not cheap – the costs of treating scoliosis can be a burden and we understand this – however the first step on the ladder, a scoliosis screening, can be incredibly cheap, or even free. A scoliosis screening involves performing just a few simple movements and standing in a normal posture while you are observed from behind – you can even use our free scoliscreen app to guide you through the process.

For those who have a family history of scoliosis, or have concerns following an initial screening, the UK Scoliosis clinic offers inexpensive initial consultations both online and in person, which are an excellent way to get a professional opinion – not just on scoliosis, but also on the case of a complaint, even if it is not scoliosis related.

We cannot stress enough that knowing your “scoliosis status” early on, makes a huge difference to your prognosis, and to the cost of care, and this is because…

Scoliosis costs more to treat, the longer it is left.

Like most conditions, scoliosis is easier – and therefore usually cheaper – to treat when its caught early on. [1] In many counties, scoliosis screenings are provided to all children at school, since it’s public health benefit is well recognised. While there is some traction for the idea here in the UK, it does seem unlikely this will become normal procedure any time soon. This is a great shame, since scoliosis can often be noticeable via a simple screening well in advance of any of the usual “symptoms” becoming visible day to day.

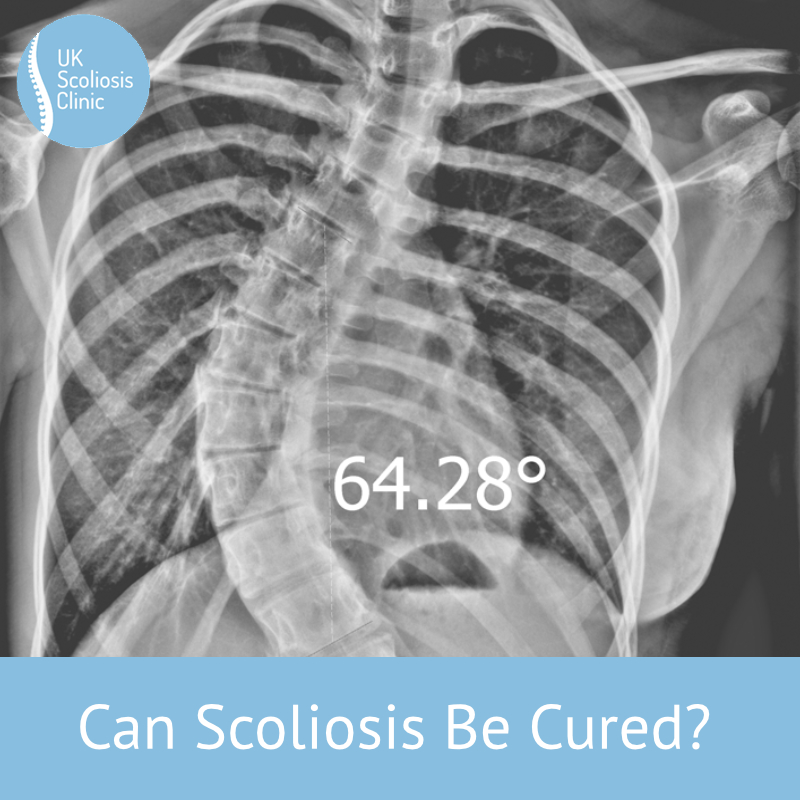

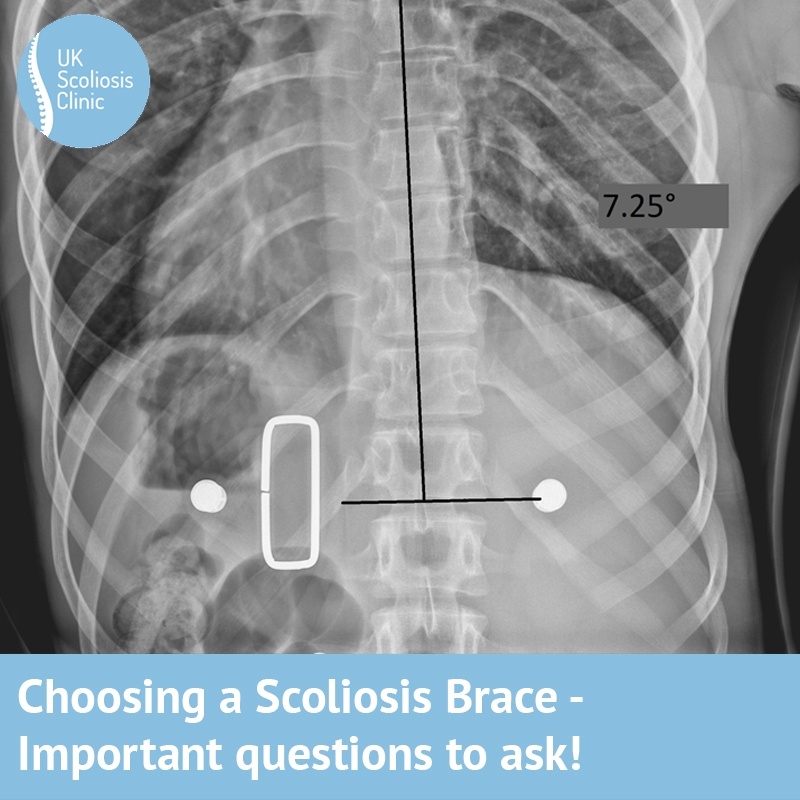

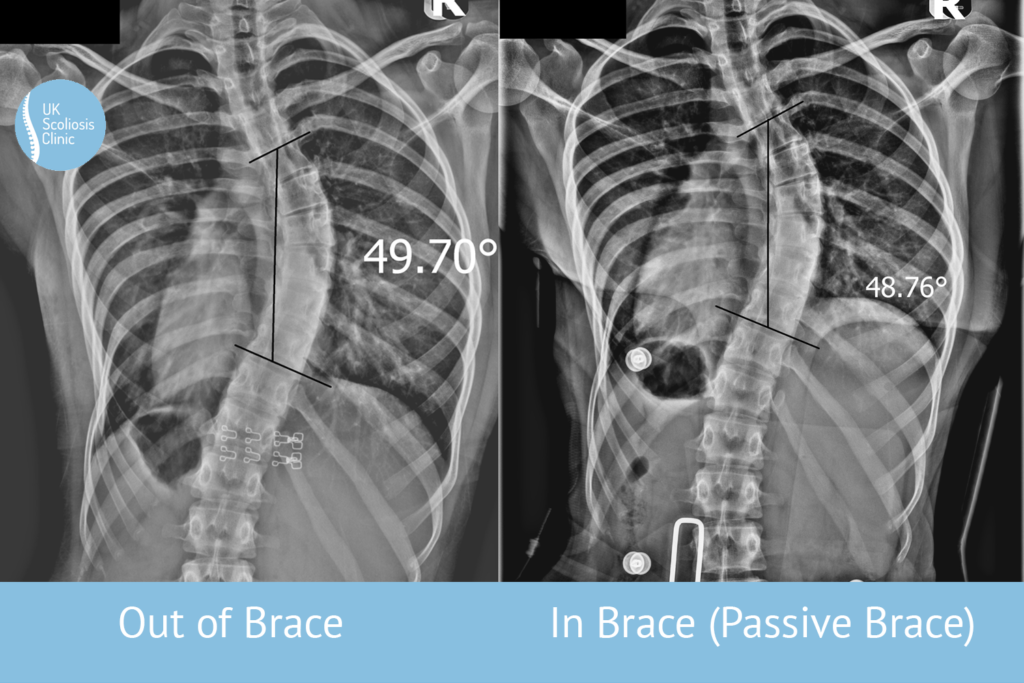

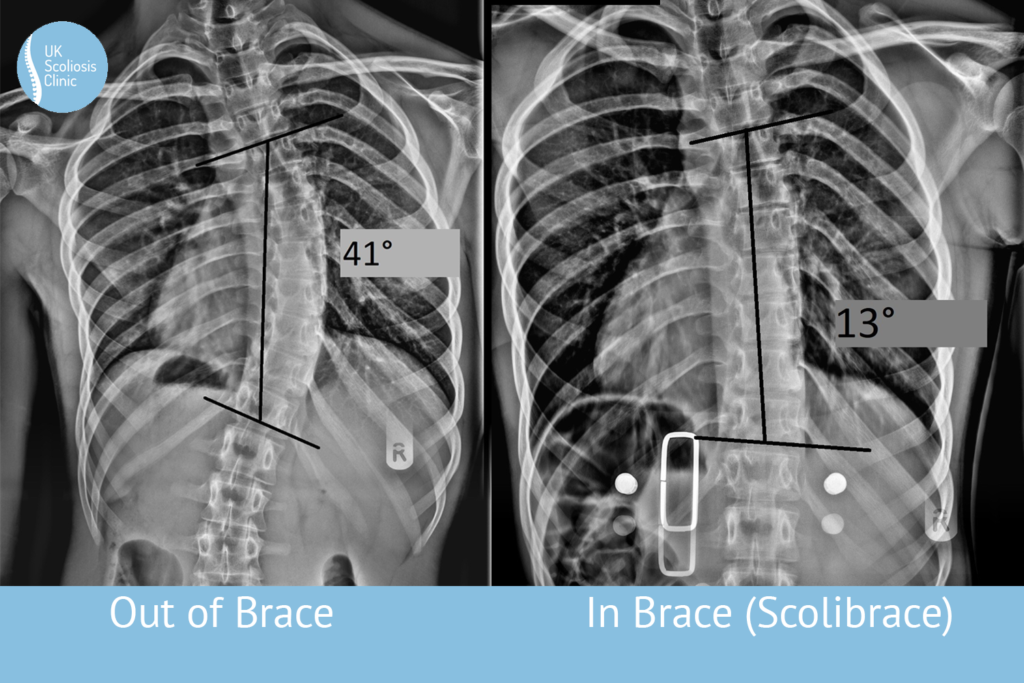

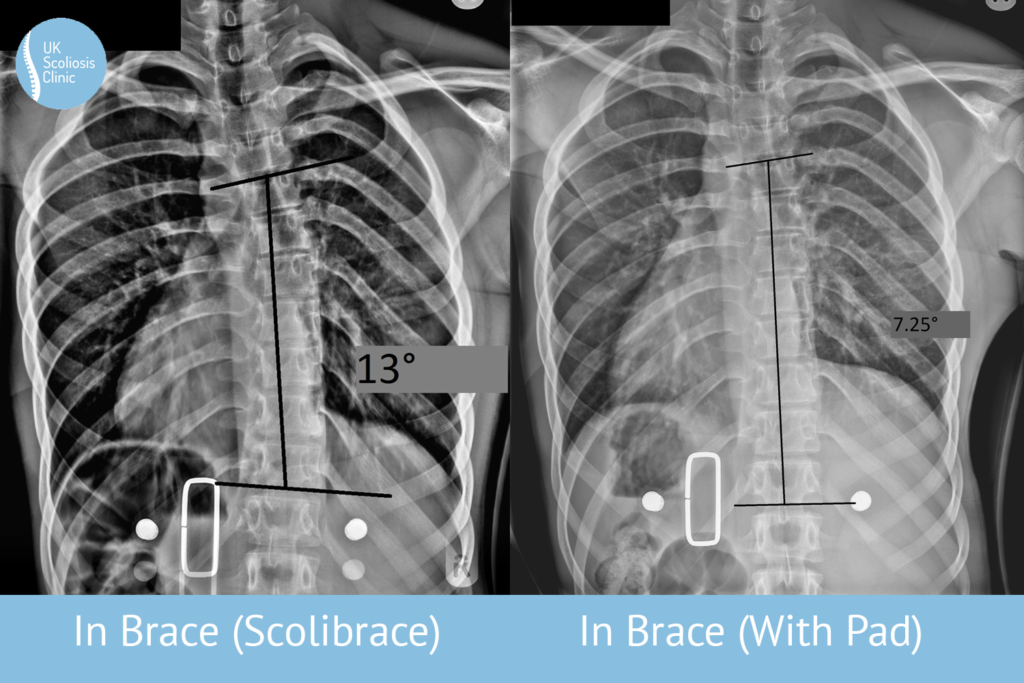

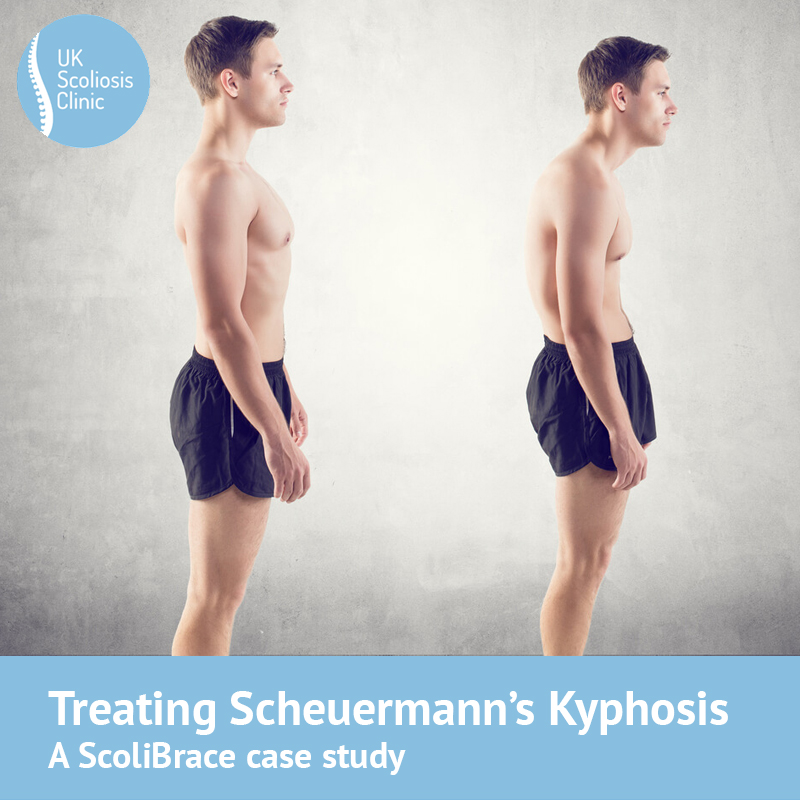

All scoliosis cases are highly individual, which is one of the things which makes it a complex condition to treat correctly – but speaking generally, If scoliosis is caught early it is often possible to treat with exercise-based approaches which usually represent the cheapest way forward. Other options for a relatively mild case include night time or part-time bracing – which, while somewhat more expensive is easier for many families to manage. Once scoliosis cases have progressed beyond approximately 30 degrees cobb, bracing will likely be the only form of treatment which is likely to succeed – while bracing is infinitely preferable to spinal surgery if at all avoidable, braces can be expensive. Innovative braces, such as our favoured model, the ScoliBrace, can help to reduce cost by extending the life of a brace through an adaptive design – but there’s no question that letting the case develop will raise the cost of treatment.

In serious cases, which have reached the surgical threshold of 50 degrees with time left for spinal growth ie curve progression, corrective bracing like Scolibrace can be used and is often successful in either reducing the curve or stopping the curve from progressing until growth has finished. This can mean that surgery can be avoided or that just one surgery can be perfomed rather than multiple surgeries that would be required as the spine grows. . Realistically, however, the costs of treating a larger curve will be higher again – often, multiple braces as well as complementary therapies will be required to achieve curve improvement.

What’s critical to remember here is that ALL scoliosis cases develop over time – all cases start out small, and therefore start out cheaper to treat. As time passes, the difficulty of treatment and the cost only rise.

So, Is surgery cheaper?

The UK is unusual, in that our NHS provides spinal surgery to those who need it – free of charge. The truth is that spinal surgery is immensely expensive – the cost of an operation to correct scoliosis would run to tens of thousands of pounds if purchased privately – but in the UK, we do not pay this cost directly. In an absolute sense then, yes, spinal surgery is cheaper – however, it’s critical to consider the social and emotional costs of allowing scoliosis to develop to the surgical threshold, as well as the possible financial implications of surgery in the long term. Especially for those who are already in work, or perhaps attending university – what would be the cost of 6 months to a year of recovery?

The other point to keep in mind here is that “opting for surgery” is not quite the same in the UK, as it would be in, for example, the US. While the NHS will provide scoliosis surgery for those in need, it will not do so for those who are not badly enough effected – this is to say, those who have reached the surgical threshold. While scoliosis does generally tend to develop over time, the rate is not always uniform and is certainly possible that an individual “opting for surgery” by simply waiting for the scoliosis to reach the threshold may actually never reach it – meaning they are left with scoliosis forever.

Don’t wait, screen today!

Scoliosis screening is free with our ScoliScreen app – and for those with concerns, affordable consultations are available at our clinic, or now even online via a secure web chat. Please do not let worries about the cost of treatment prevent you from finding out the true cause of an issue as doing so will not save money – in the long term, it will cost far more, both financially and emotionally!

[1] Fong DY, Cheung KM, Wong YW, Wan YY, Lee CF, Lam TP, Cheng JC, Ng BK, Luk KD, ‘A population-based cohort study of 394,401 children followed for 10 years exhibits sustained effectiveness of scoliosis screening’ Spine J. 2015 May 1;15(5):825-33.