New research just published by our partner ScoliCare has once again gone to show that the ScoliBrace, coupled with an appropriate exercise regime can be effective not only in reducing scoliosis, but also in treating Scheuermann’s Kyphosis.

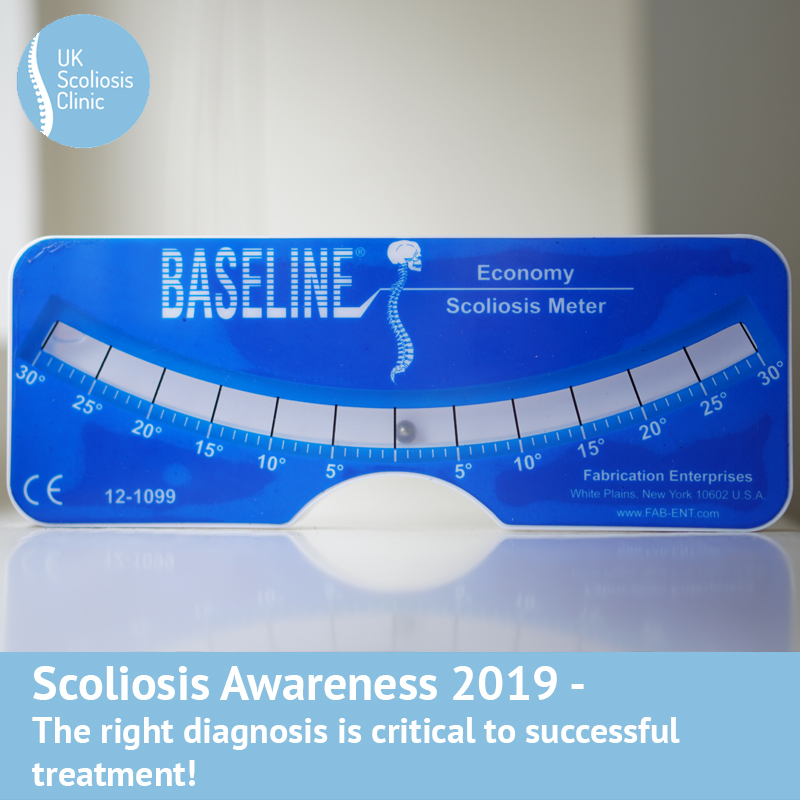

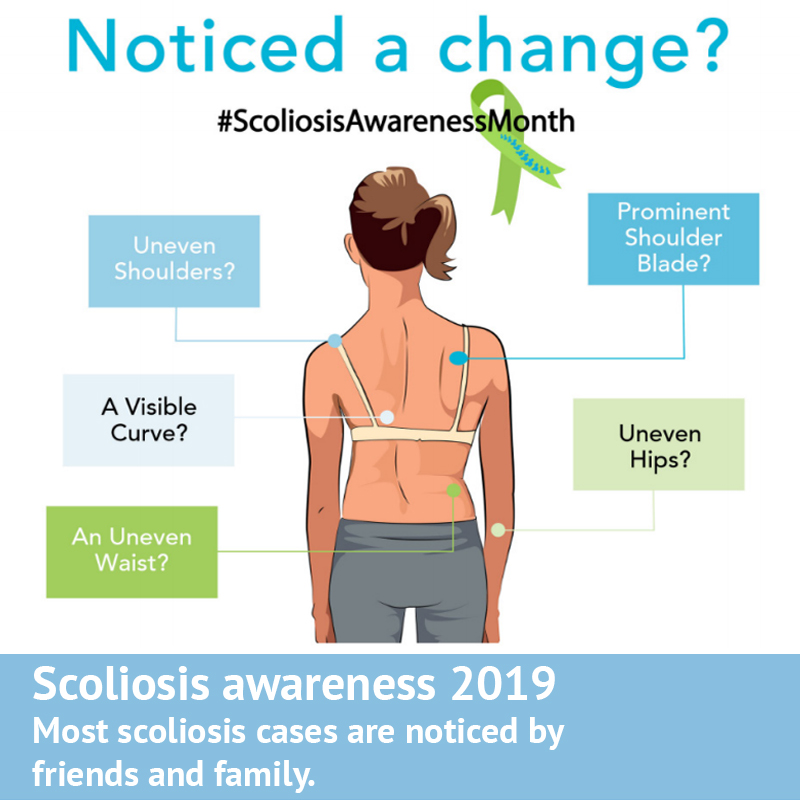

Regular readers of the blog will know that a treatable case of Scoliosis is considered to exist when the cobb angle (the bend in the spine) exceeds 10 degrees. Scoliosis causes the spine to bend “from side to side”. In Scheuermann’s Kyphosis there is a malformation of the spinal vertebrae – specifically, they are slightly shorter in height at the front than at the back, leaving them slightly wedge-shaped – This leads to a “forward hunching” curve in the spine. While both conditions can and do frequently present independently, it is entirely possible for both to be present.

With respect to treatment for Scheuermann’s kyphosis and scoliosis, a course of conservative (that is to say, non-surgical) therapy is recommended wherever possible, with surgical intervention reserved for those patients with severe pain and/or disability at the time of the initial consultation or for individuals who have not responded to conservative management attempts. The research from 2019 provided a case study of a patient in which both conditions were present, and were managed successfully with ScoliBrace, and appropriate exercise.

Let’s take a look at the recent case study[1] – both because we can learn something about the way that ScoliBrace can be used to treat these cases, but also because many readers may recognise something of their own experience!

Scoliosis and Scheuermann’s, a case study

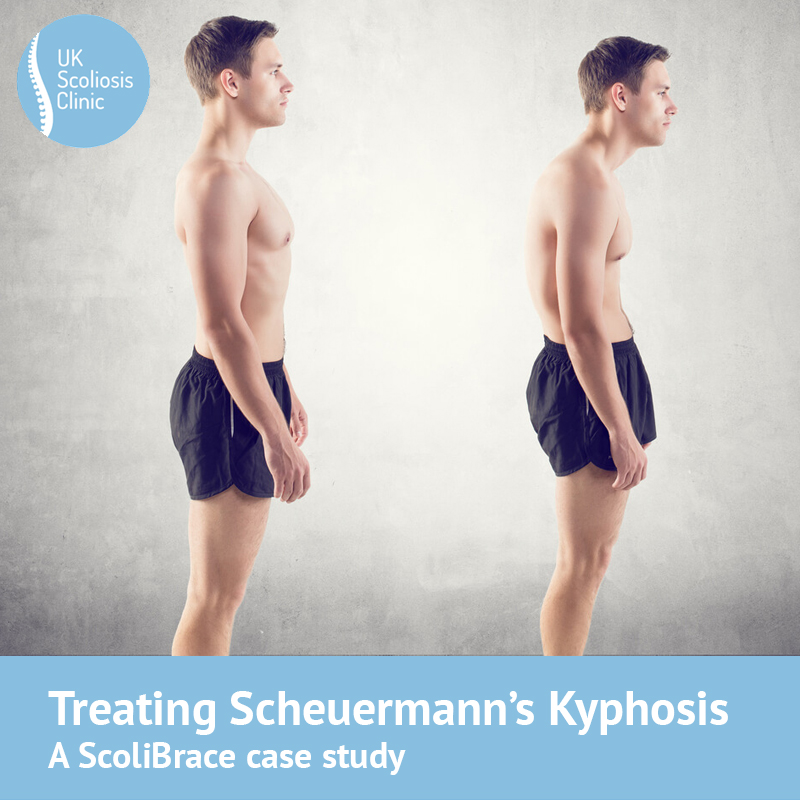

On the 22nd of February 2016, a 26-year-old Caucasian male presented to a chiropractic clinic suffering with from lower back pain and poor posture. He also had a previous diagnosis of Scheuermann’s kyphosis and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. The patient reported difficulty with prolonged standing and sitting, dissatisfaction with his cosmetic appearance, and difficulty with leisure activities – all of which are common issues for sufferers of both conditions.

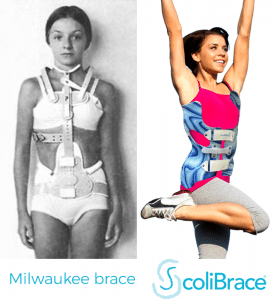

Interestingly, the patient in question had not left his spinal conditions untreated – on the contrary, at the age of 15, the patient was referred to the local Children’s Hospital and was prescribed a hospital made thoraco-lumbo-sacral orthosis (TLSO) (a brace) which he wore full-time (23 hours per day) between the ages of 15–17 years. Unfortunately, the brace provided was not like ScoliBrace, in that it’s action was preventative, rather than corrective – meaning that its objective was simply to hold his curves in place to avoid progression of the scoliosis, rather than to reduce it. The brace also had no effect on the Kyphosis.

At the point of initial examination, the patient reported that he was significantly unhappy with his physical appearance and rated his back pain as 4/10 on average and 7/10 at worst.

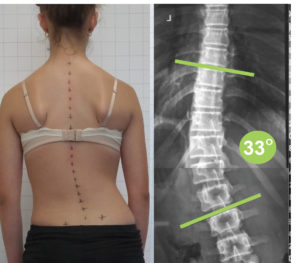

Full spine radiographic assessment was performed which revealed a thoracic hyper-kyphosis measuring 79° Cobb (Fig. 1), and a 30° Cobb lumbar scoliosis and sacral obliquity (Fig. 2). A loss of disc height, vertebral wedging and endplate irregularities were noted at several levels in the mid-thoracic spine. A true leg-length discrepancy (short left leg relative to the right) of 6 mm was also noted during the radiographic examination.

Subsequently, he was prescribed a ScoliBrace custom spinal orthosis, a rehabilitation program and a 6 mm heel lift. The ScoliBrace, unlike the Boston brace the patient was previously provide with, is an over-corrective brace, which takes and active approach to correction – this means that rather than simply trying to stop scoliosis progressing, it actually works to reduce the curve. The patients home exercises were simple for him to perform and included a mixture of stretching and strengthening exercises designed to oppose both undesirable curvatures.

12 months with ScoliBrace, results!

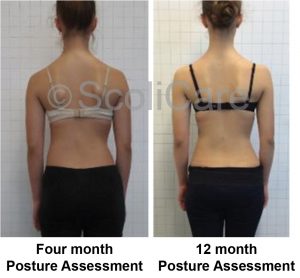

Since the entire ScoliBrace process is designed to be flexible, reactive and adaptable, patients are typically seen every 6 months or so to assess progress and make any necessary treatment changes. Our patients first follow-up assessment was performed 4.5-months after the initial assessment. After just 18 weeks, the patient reported that, on average, he had been pain-free, with his worst occasional pain being rated as 2/10 pain on occasion. In terms of the spinal deformity, the hyper-kyphosis had reduced by 16°, from 79° down to 63°, and the lumbar scoliosis curve was reduced by 5°, from 30° down to 25°.

At a further follow-up, 12 and a half months after the initial consultation, another series of x-rays showed that the postural improvements had all been maintained. An analysis of follow-up radiographic images (Fig. 6) showed a maintenance of the original postural improvements. [2]

Treating Scoliosis and Scheuermann’s at the UK Scoliosis clinic

The above case study results are interesting, because fairly few studies have addressed the use of active correction braces in adults, and there is also very little research on the correction of both conditions simultaneously. This case study certainly suggests that ScoliBrace, coupled with targeted home exercise can indeed have a positive impact on these conditions.

Of note is also the fact that this is yet another study to indicate a link between scoliosis and pain. At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we have long observed that pain and discomfort are often associated with these conditions, even if research has yet to confirm this association in an absolute sense. It would be fair to mention on this point that much of the research that would go to establish the validity of bracing as an approach to pain reduction have been affected by low adherence of study participants to their prescriptions – which is a common issue for many studies in bracing.[3]

At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we also offer the Kyphobrace system (from the same developers as scolibrace) which is ideal for treating Kyphosis cases which occur without scoliosis. To learn more, click here.

[1] Christopher M. Gubbels, DC, Paul A. Oakely, DC, MSc, Jeb McAviney, MChiro, MPainMed, Deed E. Harrison, DC, Benjamin T. Brown, PhD, Reduction of Scheuermann’s deformity and scoliosis using ScoliBrace and a scoliosis specific rehabilitation program: a case report, J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31: 159–165, 2019

[2] Christopher M. Gubbels, DC, Paul A. Oakely, DC, MSc, Jeb McAviney, MChiro, MPainMed, Deed E. Harrison, DC, Benjamin T. Brown, PhD,

Reduction of Scheuermann’s deformity and scoliosis using ScoliBrace and a scoliosis specific rehabilitation program: a case report, J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 31: 159–165, 2019

[3] See for example Weiss HR, Moramarco K, Moramarco M: Scoliosis bracing and exercise for pain management in adults—a case report. J Phys Ther Sci, 2016, 28: 2404–2407.

Palazzo C, Montigny JP, Barbot F, et al.: Effects of bracing in adult with scoliosis: a retrospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2017, 98: 187–190.