If you’ve been following the blog this Scoliosis Awareness month, you’ll know that Adult Scoliosis is generally defined as any scoliosis case that exists either in those over 18, or those having reached skeletal maturity – either definition is valid but most scoliosis specialists would prefer the latter since we are focused more on the condition itself than an arbitrary point of “adulthood.”

There are two main types of adult scoliosis. Pre-existing adult scoliosis is essentially a case of scoliosis which is continuing from an earlier age (usually adolescent scoliosis). In adulthood, a continuing case of scoliosis typically becomes known as Adolescent Scoliosis in Adults or ASA. ASA can be discovered in adults of any age, but many ASA cases are already known from treatment earlier in life.

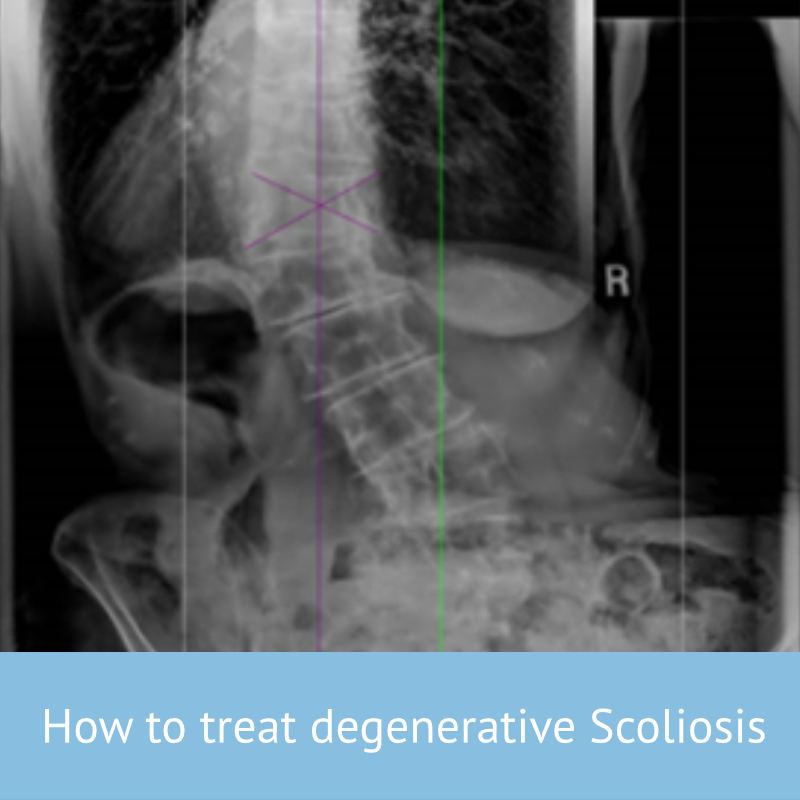

The second type is Degenerative De-Novo Scoliosis– this is the development of a new scoliosis case, usually as a result of spinal degeneration.

Much recent (and not so recent) research into scoliosis treatment, especially bracing, has focused on younger patients – this is primarily because this group stands to gain the most from bracing – proper treatment of, say a 15 year old with mild to moderate scoliosis stands a good chance of allowing him or her to live the rest of their life free of the condition. Those who have reached adulthood with a scoliotic curve, or develop one through ageing have less of a chance for improvement in the cobb angle (degree of scoliosis) but equally, lower rates of progression in the curve itself. Bracing, however, has been shown to have positive effects for older individuals, primarily around daily function and pain reduction. A recent literature review of relevant studies has confirmed this view.

What causes Scoliosis in Adults?

Since there are two kinds of scoliosis in adults, we should take a moment to understand why and how they are different.

ASA is scoliosis carried into adulthood from adolescence, isn’t caused in adulthood – it may or may not worsen depending on a number of factors, but the condition originated at an earlier point in life.

Degenerative scoliosis, by contrast, does occur in adult life and is attributable to wear and tear on the spine, but is also strongly associated with a variety of conditions. Osteoporosis, degenerative disc disease, compression fractures and spinal canal stenosis have all been implicated in the development of degenerative scoliosis.

Since De-Novo scoliosis is a consequence of spinal degeneration with age, it rarely presents before 40 years of age. For many patients, drawing a distinction between the two types may be academic at any rate, since in patients with no known history of scoliosis it may well be impossible to say whether a newly discovered case is a Do-Novo one, or ASA. It is thought that as many as 30% of over 60’s suffer from De-novo scoliosis[1], although a percentage of these cases will be undiscovered scoliosis from earlier in life. In fact, a good number of adult scoliosis cases are discovered through an investigation for another condition (such as back pain).

Recent study

The newest study[2] taking a broad view of the literature on scoliosis bracing for older adults was a review of relevant papers published between 1967 and 2018 – the study investigators used standardised criteria to select relevant papers for inclusion in their work.

In total, ten studies (four case reports and six cohort studies) were included which detailed the clinical outcomes of soft (2 studies) or rigid bracing (8 studies), used as a standalone therapy or in combination with physiotherapy/rehabilitation, in 339 adults with various types of scoliosis. Most studies included female participants only. Right away, this shows one of the biggest issues with Scoliosis research, especially in older adults – there is a clear gender bias (probably due to the higher incidence of adolescents in females, about 75% of cases) and overall a lack of research, only 8 studies considering rigid bracing of the kind now most frequently employed isn’t a huge number!

In the studies, brace wear prescriptions ranged from 2 to 23 hours per day, and there was mixed brace wear compliance reported, both are consistent with our actual experience of bracing in older adults. Most of the included studies reported modest or significant reduction in pain and improvement in function at follow-up. There were mixed findings with regards to Cobb angle changes in response to bracing.

Study conclusions

After their review, the study authors reported some key conclusions which are well worth noting. Firstly, they showed that there is evidence to suggest that spinal brace/orthosis treatment may have a positive short – medium-term influence on pain and function in adults with either de novo degenerative scoliosis or progressive idiopathic scoliosis. This finding essentially supports the use of bracing in older adults and tallies with our own experience in helping older patients to reduce and manage pain as well as improve function through bracing.

Secondly, and importantly, it was noted that a particular focus on female patients with thoracolumbar and lumbar curves made it difficult to make firm conclusions on the efficacy of bracing for males, and other curve types. It would therefore be highly desirable for further research in this area to focus on a wider variety of case types, in order for us to better understand treatment pathways for older individuals.

[1] ‘Scoliosis in adults aged forty years and older: prevalence and relationship to age, race, and gender‘

Kebaish KM, Neubauer PR, Voros GD, Khoshnevisan MA, Skolasky R, Spine 2011 Apr 20;36(9):731-6.

[2] Jeb McAviney et al. A systematic literature review of spinal brace/orthosis treatment for adults with scoliosis between 1967 and 2018: clinical outcomes and harms data BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 21, Article number: 87 (2020)