Early-onset Scoliosis is an umbrella term used by many organisations (including the scoliosis research society) to include scoliosis cases that present under the age of 10. Within this bracket, there are really two further categories of scoliosis we need to understand.

The first is Infantile scoliosis – which is the name given to scoliosis cases that are diagnosed in children between the ages of 0 to 3 years. Infantile Scoliosis is at least as common in boys as girls, which is worth bearing in mind since adolescent cases (which comprise the majority of overall cases) are predominantly female cases[1].

Juvenile scoliosis is therefore diagnosed when scoliosis of the spine is apparent between the ages of 4 and 10. It is less common than adolescent scoliosis and comprises about 10-15% of total idiopathic scoliosis cases. It is found more often in boys between the ages of 4-6 and curves tend to be left-sided, while in older children it is more common in girls and curves are right-sided and similar to adolescent scoliosis.[2]

What causes early-onset Scoliosis?

There are several main categories that comprise early-onset scoliosis cases – these are:

- Idiopathic – Curves for which there is no apparent cause – this is probably the kind of scoliosis you are most familiar with, as it forms the bulk of scoliosis cases, especially in teens.

- Congenital – Here the cause is incorrect development of the Vertebrae in-utero. It is sometimes associated with cardiac and renal abnormalities.

- Neuromuscular – In children with neuromuscular disorders including spinal muscular atrophy, cerebral palsy, spina bifida and brain or spinal cord injury.

- Syndromic – Certain syndromes, such as Marfan’s, Ehlers-Danlos and other connective tissue disorders, as well as neurofibromatosis, Prader-Willi, and many bone dysplasias may be associated with EOS.

At the UK Scoliosis clinic, we mainly focus on the treatment of the idiopathic variety – which, as the name implies, is currently without defined cause. There are two main theories that explain the development of idiopathic infantile scoliosis – the first postulates that some children are simply born with a spine that is already curved, while the second suggests that the curvature occurs after birth and may be linked to the way a baby is handled. Much more research is required to clarify this, however.

What is the prognosis for early-onset Scoliosis?

The Scoliosis research society notes especially for early-onset cases, that early Scoliosis carries a risk of heart and lung problems in childhood which may become increasingly problematic in adult years[3] – but it’s worth noting that other research has shown that scoliosis can negatively impact the heart and lungs as the deformity increases in other age categories[4]. When untreated, severe EOS may be associated with an increased risk of early death due to heart and lung disease – the term Thoracic Insufficiency Syndrome (TIS) is commonly used to describe the potential combined spine and lung problems in EOS.

Idiopathic scoliosis has a number of possible treatment pathways, both non-surgical and surgical, whereas congenital and syndromic cases are more complex, and require in-depth evaluation to determine the best pathway. In all instances, it is important that suspected cases in infants should be investigated with a complete neurological examination and MRI or CT scan. This will serve to rule out any underlying neurological condition or disease process and allow the best treatment to be given as soon as possible.

How can we treat early-onset scoliosis?

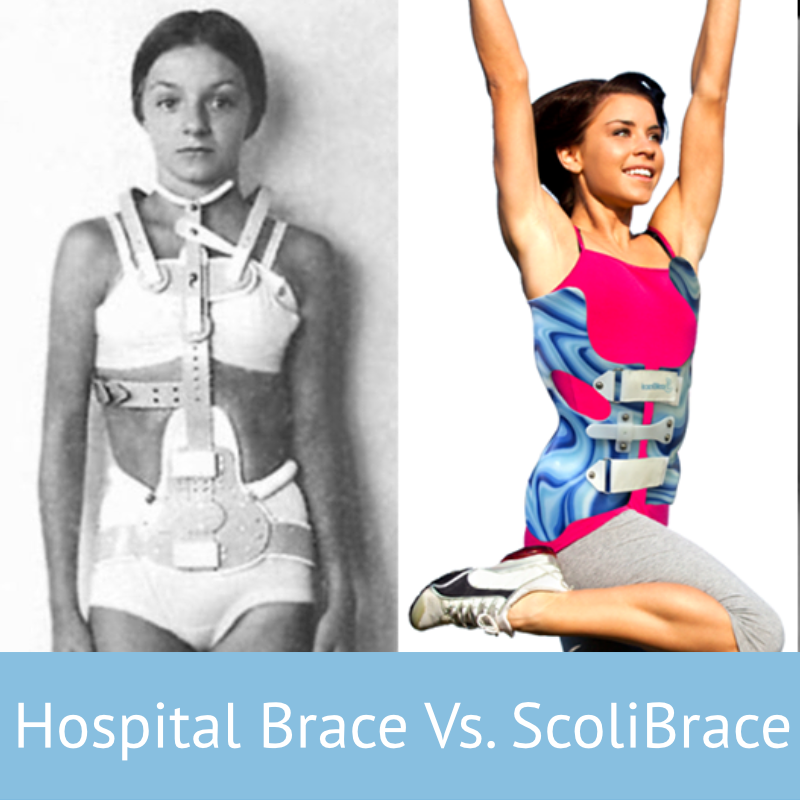

Bracing may be an effective approach in idiopathic cases with good flexibility in the curve – however, rigid curves are less likely to benefit from this approach. Casting (which is a similar approach, using a plaster cast rather than a brace) is also a possible approach here.

Early-onset scoliosis is, however, the only broad category of scoliosis where the “wait and see” approach may have some value. The Scoliosis research society guidelines suggest that Idiopathic early onset scoliosis with curves greater than 30-35 degrees are most likely to progress and some studies have suggested the progression to surgical threshold for this group may be as high as 100%[5] – however, children younger than age 2 with infantile idiopathic curves less than 35 degrees stand a chance of the condition resolving without further treatment.

What does early-onset Scoliosis look like?

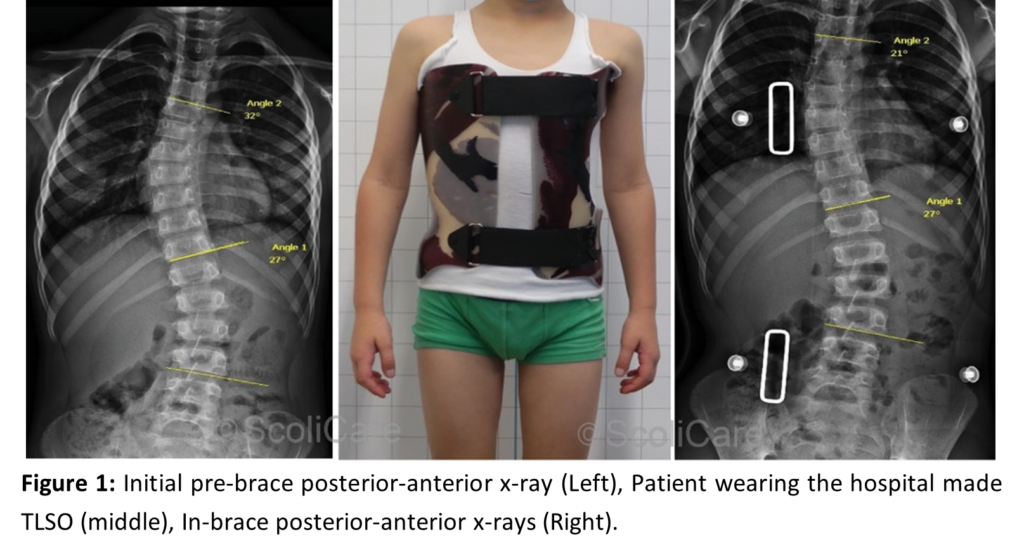

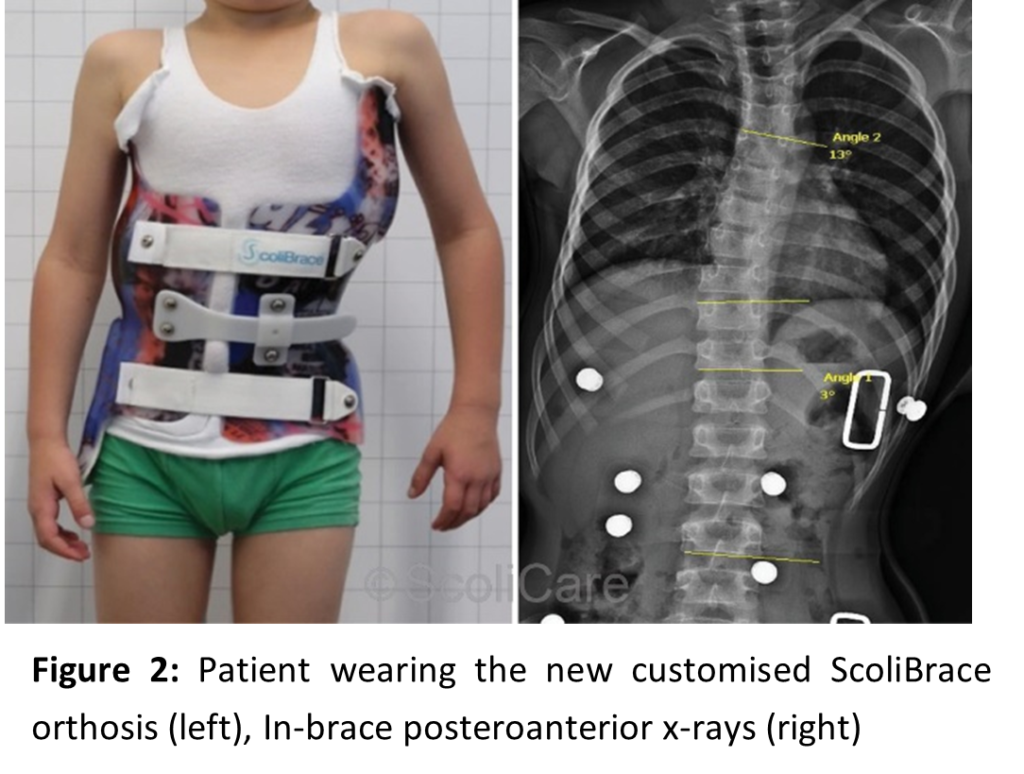

The below X-ray shows an example early onset Scoliosis case. It’s usually not possible to tell how severe scoliosis is without taking an X-ray, although external signs can suggest that the condition may be present. This is why regular screening is so important!

[1] https://www.srs.org/patients-and-families/conditions-and-treatments/parents/scoliosis/early-onset-scoliosis/infantile-idiopathic-scoliosis

[2] https://www.srs.org/patients-and-families/conditions-and-treatments/parents/scoliosis/early-onset-scoliosis/juvenile-idiopathic-scoliosis

[3] https://www.srs.org/patients-and-families/conditions-and-treatments/parents/scoliosis/early-onset-scoliosis

[4] Sperandio EF, Alexandre AS, Yi LC, et al. Functional aerobic exercise capacity limitation in adolescent idio- pathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2014;14(10):2366–72. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.01.041

Sperandio EF, Vidotto MC, Alexandre AS, Yi LC, Gotfryd AO, Dourado VZ. Exercise capacity, lung function and chest wall shape in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Fisioter Mov. 2015;28(3):563–72. doi:10.1590/0103-5150.028.003.AO15

Barrios C, Pérez-Encinas C, Maruenda JI, Laguía M. Significant ventilatory functional restriction in adoles- cents with mild or moderate scoliosis during maximal exercise tolerance test. Spine. 2005;30(14):1610–5. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000169447.55556.01

[5] Progression risk of idiopathic juvenile scoliosis during pubertal growth, Charles YP, Daures JP, de Rosa V, Diméglio A. Spine 2006 Aug 1;31(17):1933-42.